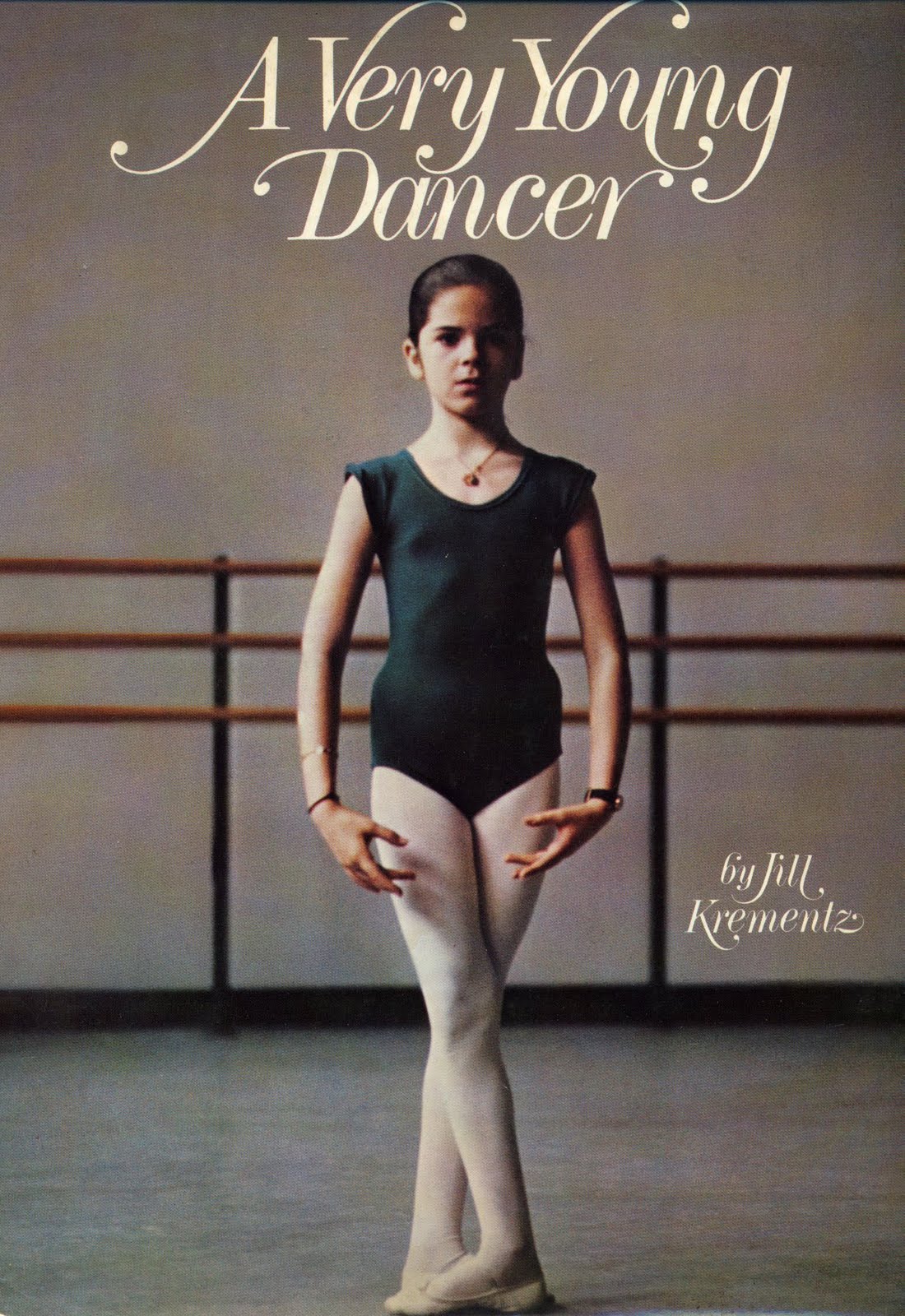

When I was a kid, I was semi-obsessed with the photographer and author Jill Krementz. She was most famous for a series of book length photo essays in which she profiled kids who excelled at various sports and creative endeavors, told through their own words and with candid photos of them living their lives. There was “A Very Young Dancer”, “A Very Young Gymnast”, “A Very Young Skater”, “A Very Young Circus Flyer”, and a few more, but not enough for me. I used to go back to the shelves where they were kept in the children’s room in the library when I was 6 or 7, and will for another one to appear, I loved them so much. I liked projecting myself into what I perceived as their very exciting daily existences (okay, a bit of wish-fulfillment) but I also just liked the combination of words and images about real kids’ lives. Most picture books I read as a child were fiction, and the non-fiction kids’ books available were mostly full of straight facts, not good storytelling. These books stood apart.

A few years later, I stumbled upon another series she wrote, called “How It Feels…” “How It Feels To Fight for Your Life,” “How it Feels to be Adopted,” “How it Feels When Parents Divorce.” Once again, but in a different way, I was fascinated by the first person accounts by regular kids of what it was like to go through challenging experiences I had never been through. The interviews were paired with straightforward black and white images of the kids, and again I kept scouring the shelves for more volumes.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that series lately in relation to my current work. Another title for Grief Landscapes could be “How It Feels to Grieve” (which Jill Krementz essentially did a version of, with “How It Feels When a Parent Dies”). What I find myself drawn to again and again is people telling their own stories, in their own words, about things that we often don’t give ourselves permission to talk about.